Pandemic’s baby bust part of long-term decline in birth rates

Falling birth rates can lead to slower economic growth as fewer people are available to enter the workforce

MICHAEL CRUMB Mar 15, 2021 | 4:15 pm

5 min read time

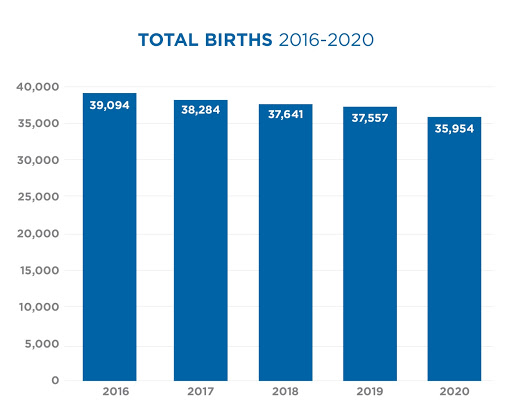

1,291 wordsAll Latest News, Economic Development, Health and WellnessIowa births from 2016 to 2020. Source: Iowa Department of Public Health

What some had thought might be a baby boom as people hunkered in at home for work and play as the coronavirus spread across the country has likely turned into a baby bust, according to a recent report from the Brookings Institute.

According to the report, the lockdown that occurred as the virus tightened its grip on the country will likely lead to a decrease of as many as 500,000 births in the U.S. this year.

One thing is clear: Although people were isolated at home as restaurants, entertainment and sporting venues closed, and as most people were relegated to remote-work status, that closeness didn’t result in more babies being born.

“It’s a charming idea,” Susan Stewart, a professor of sociology at Iowa State University, said of the notion that there would have been a baby boom during the pandemic. “We hear about blizzard babies, hurricane babies and blackout babies, and there might be a tiny uptick in births for a very minor event, like a blizzard or something, but when you have a huge calamity, like an economic recession or pandemic, you see just the opposite.”

Stewart said birth rates dropped during the Great Recession and never recovered.

“It didn’t bounce back up,” she said.

The Brookings Institute report looked at data from 29 state health departments, and in June — three months after the virus began to shut down the country — it issued a report that predicted a big drop-off in birth rates. An update to the report suggests those numbers could be even higher as school and day care closures lingered into the fall and early 2021.

According to the authors of that report, their data did not include Iowa, so we reached out to the Iowa Department of Public Health, which provided the state’s birth rate data for 2020 and January 2021. Doing the math, the possible impact of the pandemic on birth rates would first be seen in December 2020 and January 2021.

For both of those months, birth rates fell from the same month the year before, with the numbers in January 2021 compared with January 2020 representing a drop of more than 11%. There were 3,053 births in January 2020. In January of this year, that fell to 2,793.

The numbers are only preliminary and could change as more births are registered with the state. That data for subsequent months isn’t released until 30 days after the end of the month, so birth numbers for February 2021 won’t be known until the end of March.

Something to note: Although the numbers for the early months of the pandemic appear to be down, birth rates in Iowa have been declining for several years.

According to state records, the number of babies born in Iowa has declined fairly steadily since 2016, when 39,094 children were born. That number dropped to 35,954 in 2020.

Stewart said birth rates in the U.S. have slowly been declining for at least the past 50 years.

The decline is the result of increasing levels of education and employment opportunities for women, and shifting gender roles, she said.

“In high-fertility societies, the status of women is low. In low-fertility societies, the status of women is higher,” Stewart said.

With the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic, people are less apt to conceive and bring a child into the world, she said.

“Children are just really expensive, so when there’s a lot of uncertainty, … we have a lot of control over fertility and people are thinking this is not the best time to start thinking of having kids or have more kids,” Stewart said.

The pandemic, she said, has “laid bare” disproportionate effects on women and the juggling of job, child care and housework, and that could further affect the decline in births.

Stewart said nationally, the U.S. population would be in decline if it weren’t for immigrants moving here.

“Our birth rate is 1.8 children per woman in the U.S.,” she said. “And we don’t even know the effect of the pandemic because we don’t have the numbers, but if you’re below 2.1 children per woman, your population is going to decline.”

If you add immigrants, the U.S. population is growing slightly.

She said countries like Japan and some European countries where populations are declining are concerned about the economic effect of lower birth rates.

“People are worried about who’s going to work all these jobs, and who’s going to support the elderly and how are we going to pay all these health care costs,” Stewart said. “The U.S. has always had slightly higher fertility than other industrialized countries … but now we’re right down with all of them.”

Tom Root, associate professor of finance at Drake University, said declining birth rates can have a long-term effect on economic growth.

“There’s three big drivers of growth: labor, capital and productivity,” he said. “Declining birth rates slows down that growth in the labor portion, which feeds into employment, which feeds into our output.”

That is offset by advancements in technology that help workers be more efficient and increase productivity, Root said.

Slowed economic growth is one consequence of declining birth rates. It also changes the Social Security structure. With more people in the U.S. living longer and being retired longer, fewer people are contributing to the system to support those benefits, he said.

“That creates a bigger tax on people to keep up the same benefits, so you have public policy outcomes like that that can contribute to economic growth,” Root said.

He said short-term declines, like what may happen because of the pandemic, more often affect things like school enrollment and decisions on whether to build a new school, but don’t affect long-term economic growth.

Immigration is another factor that is important for the country’s long-term economic growth, Root said.

“We need immigrants coming in to have some of that population growth to help the economy grow,” he said. “We actually kind of need that. It’s an interesting paradox there.”

Root said the long-term trend of declines could cause a shift in the world’s population centers.

“That can have a 50-year, 100-year impact in the way the world economy grows,” he said.

Stewart said continued declines in birth rates with the state’s aging population, and an economy where young people leave the state after graduation don’t bode well for the state’s ability to make up ground in population.

The Iowa Business Council’s Competitive Dashboard released last month showed that the state experienced a decline in population last year, the first time that has happened since the organization began publishing the report in 2011.

“I think it’s concerning, for sure,” Stewart said. “Look at higher ed in Iowa, Gen Z is a small generation and enrollment is going down. There just aren’t enough bodies.”

Stewart questioned whether people will eventually make up for the decline that apparently is happening because of the pandemic.

“Are we ever going to see those kids being born?” she said. “Maybe. Maybe not. We don’t know how long we have these negative effects of the pandemic.”

She projected that the 11% decline seen in January will continue until more people are vaccinated.

“Women don’t want to get pregnant when there’s a health crisis out there,” Stewart said.

Marriage rates also have been declining, which contributes to the decline in birth rates. In Iowa, there were 15,484 marriages in 2020, down from 19,277 in 2016, state public health records show.

While some babies are born outside of marriage, the majority are born in a marriage.

“People are putting off marriage too, so then you have an even longer delay to have children,” Stewart said.