A long haul to green

Tony Colosimo and Tom Hadden need no introduction – to each other.

And they are familiar names to business people and government leaders interested in trash and the various things that can be done with it: put it in a landfill, recycle it into compost, burn it for fuel.

If you’re just dumping last night’s leftovers in the garbage, you might not give them a second thought.

They are two men knee-deep in the trash business who have become legal opponents in a form of trash talk generated by differing views on how and what to recycle. Both seek an environmentally friendly future where all of our garbage that can be recycled will be recycled.

They are “green” by a contemporary definition. They both embrace the term, but also recognize that it is a euphemism for seemingly worthwhile environmental goals, not all of which are achievable or easy to whitewash with an adjective that conjures visions of bluebirds and wildflower prairies.

“We’re still in the garbage business,” Colosimo says. “We haul it and they collect it.”

For his part, Hadden says that “you can’t take all waste and spin it into gold.”

Who are these guys?

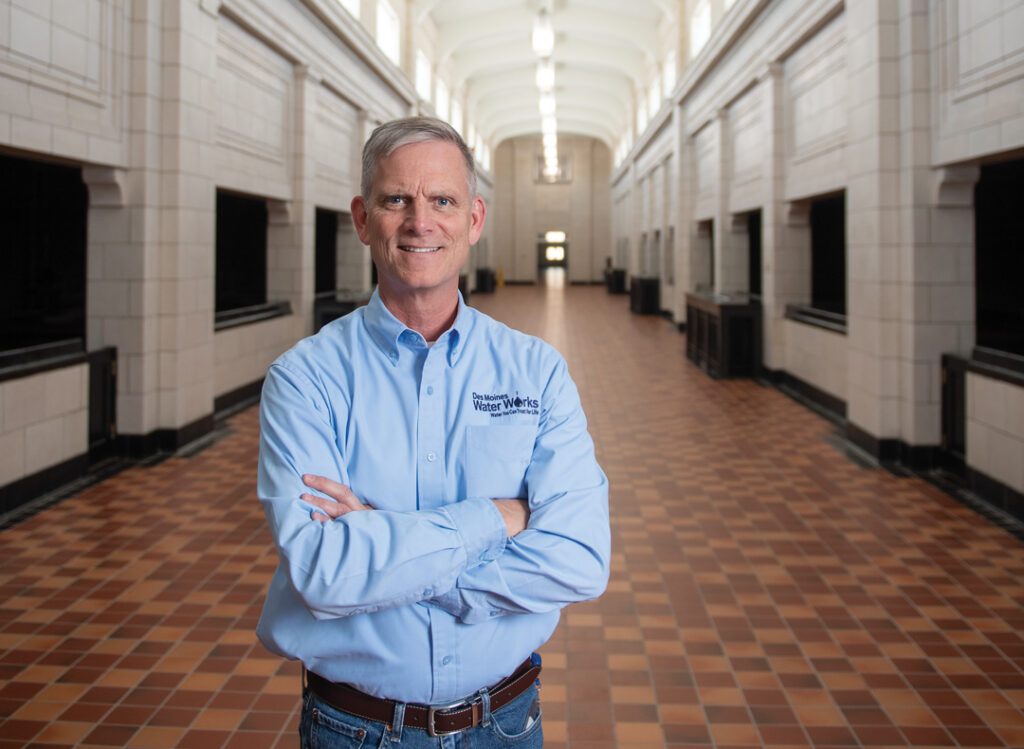

As a private businessman, Colosimo has launched or bought enterprises that recycle everything from wood trusses to envelopes. He also is chief executive of Artistic Waste Services Inc., a company he bought in the 1990s after deciding that the food industry was “too cutthroat.”

His college degree is in marketing. He is gregarious and determined. He is pugnacity with a smile. It would be difficult to imagine him losing many “cutthroat” disputes.

Colosimo said that when he bought Artistic, the largest trash hauler in Greater Des Moines, he really had his eye on a recycling operation.

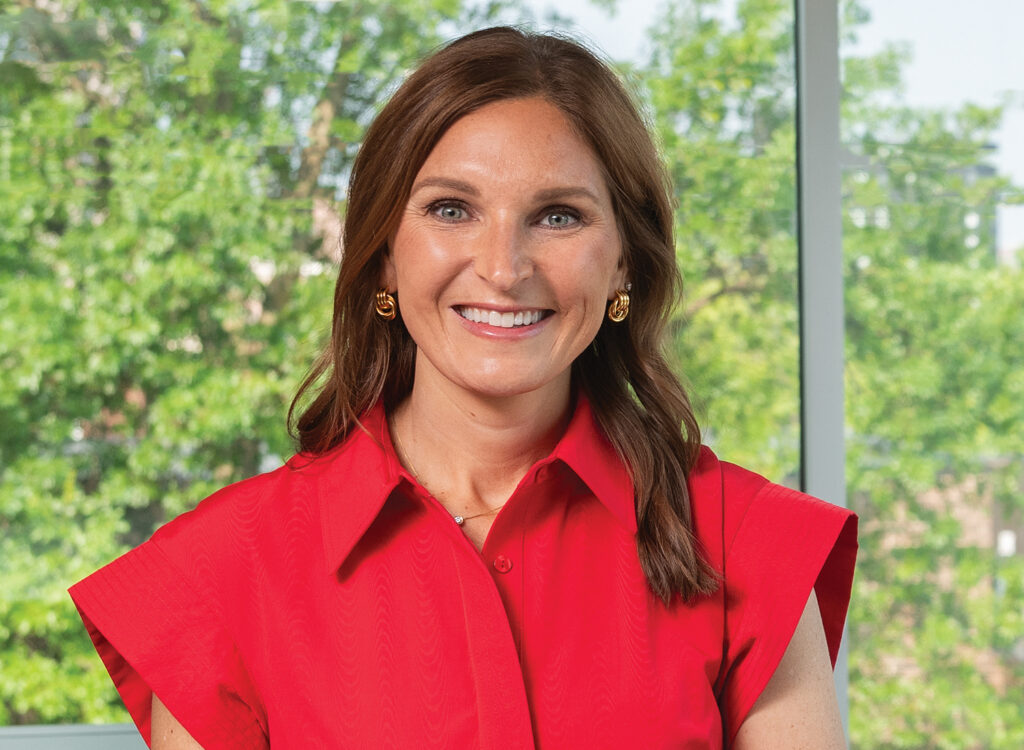

Hadden, as executive director of Metro Waste Authority, operates a landfill that is part watershed, part prairie, part farmland.

Metro Waste would serve as a model for a small business. It is creative; it sponsors an annual 5-kilometer run/walk and a 10Krun that exposes Greater Des Moines residents to what is frequently described as the diamond in the rough of U.S. landfills. Its headquarters are in a new building in the East Village, where it also leases space to nonprofit organizations and private businesses.

The landfill generates income beyond the tipping fees it charges trash haulers by sharing the profits from the 800 acres of corn and soybeans and switchgrass harvested on its 1,800-acre spread in eastern Polk County. Just 500 acres are set aside for trash.

Hadden is a former city administrator in Altoona. He initially trained to become a crime scene expert for the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He has degrees in environmental engineering and business administration.

He is soft-spoken and measures his words. He would like to put his conflicts with Colosimo in the past. He doesn’t want to get involved in a public “I said, he said” dispute with Colosimo. Those debates have been carried out in Polk County District Court.

Both men say they hold no grudges against the other; they just have found themselves on opposite sides of one battlefront in the green revolution.

Shared history

Their story dates to 2004, when Colosimo bought Phoenix C & D Recycling Inc. to process debris from construction and demolition sites. The company has been renamed Phoenix Recycling Inc.

The business appeared lucrative. At the time, Metro Waste was entertaining proposals from Greater Des Moines companies that said they could find markets for the debris and reduce what was left over into a soil-like substance that the landfill could use to cover its daily intake of garbage. That material is called alternative daily cover.

Metro Waste initially considered running its own operation, but yielded to requests from Colosimo and representatives of the former Regency home building company to let private enterprise lead the way.

There has been more than one occasion when Metro Waste officials have regretted that decision.

Problems arose almost from the start, with Metro Waste arguing that the alternative daily cover amounted to more than ground-up bits of soil, stone and wood. Other materials were mixed in with the product, which Metro Waste said it would accept for free providing it met certain standards.

The material arrived at the landfill containing large quantities of gypsum wallboard, which creates a sulfur-like odor when it decomposes.

Someone driving by the landfill objectedto the odor, and both Phoenix and and the now-defunct Environmental Reclamation & Recycling were notified by Metro Waste that they were in violation of a contract with Metro Waste and would be charged normal landfill fees if they delivered the material.

Colosimo maintains that Hadden was the passer-by who noticed the foul odor. Hadden said that is not true. Even if he had, so what? Hadden is a neighbor, and the landfill has other neighbors who don’t hesitate to complain if trash scatters or they suspect other problems. It should be noted that Metro Waste also has installed large screens that capture wind-blown trash before it can scatter to Iowa Highway 163, which passes north of the landfill.

Metro Waste also recently completed a full-scale review of all of its recycling programs and recycling vendors after two women expressed concerns at a meeting of the agency’s board of directors.

Back to the past

Phoenix filed a lawsuit in 2006 claiming that Metro Waste arbitrarily changed the conditions of the contract that it signed with construction demolition companies. It also sought to have a judge order a redrafting of the contract. And it claimed that Metro Waste’s concerns about odor were misplaced, possibly based on bad or manipulated science.

Phoenix lost at every turn of that lawsuit. It lost in arbitration. It lost in the decisions of two judges who heard different aspects of the case. It appealed, and recently lost the appeal. It has asked for further review before the Iowa Supreme Court.

Phoenix also is losing with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR), which regulates landfills and solid waste processors.

Earlier this year, an administrative law judge with the Iowa Department of Inspections and Appeals ruled that the DNR was within its rights when it revoked Phoenix’s operating permit, which had been scheduled to expire June 18.

The permit had been issued in 2007, and within a few months DNR inspectors determined that Phoenix was in violation of conditions of the permit, primarily because it had stockpiles of ground-up wood stored outside its headquarters on Northeast 22nd Street.

Colosimo argues that the wood pile was a processed material and should not be classified as waste. The DNR disagreed; so did the administrative law judge.

The case has dragged on for so many years and generated so much paperwork that a DNR attorney has created a website where members of the department’s policy-setting Environmental Commission can easily find all of the documents related to the case.

Colosimo has appealed the judge’s ruling to the commission, which has set a hearing for July 20.

DNR attorney Jon Tack said it is likely that Phoenix will appeal any ruling against it. If the commission upholds the judge’s ruling, Phoenix can appeal to state court. However, it will not be able to continuing operating under its permit without seeking a special order from a state court judge.

The DNR also will appeal if the commission rejects the administrative law judge’s ruling, Tack said.

The DNR hopes that at some point the Legislature will pass a law that requires contractors to separate debris on site, rather than sending it to a processor such as Phoenix to be separated and processed, he said.

Colosimo would oppose that, viewing it as another intrusion by government and regulators into affairs best left to the discretion of private businesses.

It is convenient for contractors to have the material separated by Phoenix, which charges them $42 a ton for disposal at its processing facility.

Colosimo said Iowa stymies the development of markets for the material, which he sells to companies in neighboring states that burn it for fuel. He would get out of the business if he didn’t believe there were more markets to tap.

“I know that recycling is going to be the place where you want to be,” Colosimo said.