Charting a course

DART continues search for alternative funding as funding gap, possible service cuts loom

Michael Crumb Sep 15, 2023 | 6:00 am

8 min read time

2,018 wordsAll Latest News, Business Record Insider, TransportationThe Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority will soon be reaching out to learn more about what the community wants from public transportation as the agency continues efforts to address a funding gap it could face in fiscal year 2025.

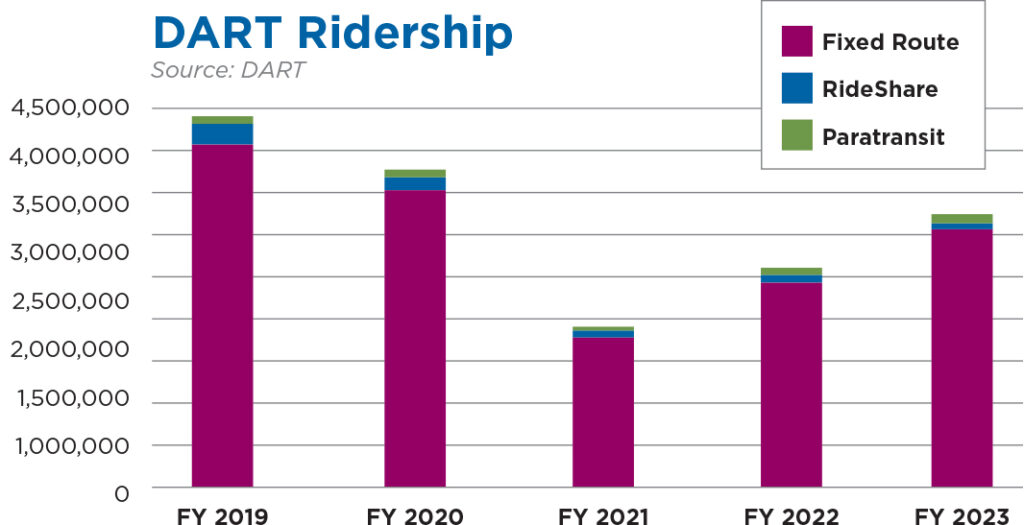

The agency, commonly known as DART, provided 3.2 million rides in fiscal year 2023, which ended on June 30. That is up 20% from the prior year, but still lags behind pre-pandemic levels — down about 31% — when the agency provided about 4.4 million rides in fiscal year 2019.

According to DART, 57% of its riders take the bus to and from work; 61% of riders don’t have a driver’s license; and 61% don’t have a working vehicle in their household.

It’s those kinds of numbers that leaders of DART turn to as a way to emphasize the importance public transit plays in economic and workforce development.

Funding

DART’s current operating budget is $42 million. Under its current formula, 62% of revenue comes from property taxes. The remainder comes from a combination of federal funding, fares and contracts, state funding and other sources. With so much of its revenue coming from property taxes, DART finds its hands tied because the property tax levy for DART is capped at 95 cents per $1,000 valuation.

While the Legislature earlier this year gave the city of Des Moines permission to increase its franchise fee from 5% to 7.5% to provide additional revenue for DART, the City Council has yet to approve that move. The city has been paying above the 95% property levy cap for DART funding from other sources.

Efforts to tap into other sources of revenue, such as hotel-motel tax revenue or sales tax, to reduce the burden on property taxes, have so far been unsuccessful, leaving officials at DART looking at how it can stave off the funding gap that is forecast to materialize in fiscal year 2025, which begins July 1, 2024.

The magnitude of the funding gap isn’t clear and will depend on whether service cuts are made or if alternative funding is approved by the Legislature.

In the coming weeks and months, DART leaders will be reaching out to local and state elected officials, business leaders and the public as it works to chart a course forward.

“What road we may have to take, depending on the state, we will look at what some reductions in service could potentially look like and what’s going to be the least disruptful,” said Russ Trimble, chair of the DART board of commissioners and mayor of West Des Moines. “I think that’s where we’re at, looking at different scenarios and looking at different hypotheticals as we try to prepare.”

If Des Moines increases its franchise fee, it’s unclear how much of a dent that would make in the shortfall, he said.

“We’re continuing to take a look at that and analyze that,” Trimble said.

He said DART either has to find alternative funding sources or make reductions in service to balance its budget.

“We are so reliant on property tax revenue of all the member communities, and the revenue just isn’t growing enough to support the service,” Trimble said.

Amanda Wanke, CEO of DART, said the goal of the upcoming conversations will be to bring people together to reach “a shared vision of what it could be like and how public transit can have the most impact to drive our economy and our community forward.”

Wanke, who recently rejoined DART as its CEO, said it will be important to elevate community awareness to the important role public transit plays as an “essential economic driver” for the region, “and a good return on investment for taxpayers.”

“We have to win over those hearts and minds to really believe that public transportation is that essential economic driver,” she said.

Wanke and Trimble said the opportunities that DART is facing will be the latest as public transit has evolved from the days of street cars.

“We’re at a unique time in our history,” Wanke said. “You look at how transportation has changed.”

From streetcars to electric buses

To learn more about the evolution of public transportation in Des Moines, the Business Record reached out to Earl Short, a local public transit historian who founded the Des Moines Streetcar Friends to keep the memory of the streetcar era alive.

That effort includes the new Waveland Trolley Loop monument on University Avenue that features an interactive streetcar sculpture, a small park and informational panels.

Short, now 85, recalls riding the streetcar with his father as a child. His father operated a streetcar from 1923 to 1961. By the time his father retired, buses had long taken over from street cars.

Public transportation started with horsecars, a streetcar pulled by horses on rails. That was around 1866. By 1888, streetcars motored by electric engines began to take over when the Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company of Richmond, Va., built an electric motor to power streetcars.

The transition to buses happened in 1938, although some buses operated alongside streetcars since the early 1920s, Short said.

Buses were quieter and didn’t use rails, allowing them to pull right up to the curb to let passengers board without having to walk across muddy roads, Short said.

The advent of the bus coincided with streets being paved, he said.

As World War II progressed, streetcars made a brief return as the rubber used for bus tires was needed by the military. But once the war was over, buses returned to the city’s streets, Short said.

Public transit has always been considered an economic driver for the community, he said, first carrying passengers to parks on the outskirts of town.

One park was Ingersoll Park, at the intersection of Ingersoll Avenue and Pok Boulevard.

“It was a very popular park nationwide,” he said. “The first weekend they were open, they were running 30,000 to 40,000 people a day and they were bringing them out on the streetcar.”

Another park was on East 33rd Street on Des Moines’ east side, Short said.

“It was only a nickel for people to ride the streetcar at that point, and they’d get into the park for free,” he said.

Public transit later evolved to being a primary way for people to get to and from work, not unlike how it’s used today, Short said.

“Houses started building in and people needed to get to work,” he said. “They would take the streetcar to the fair or to church.”

Use of public transportation began to decline after World War II ended, when production of cars increased, and more people bought cars to get around, Short said.

He said his father would probably be humored by the introduction of electric buses by DART as a pilot project in recent years.

“We’ve gone full circle,” Short said. “He was there with electric streetcars.”

The future

Trimble said DART officials will continue to search and advocate for alternative funding sources to prevent possible reductions in service to customers.

“We’re exploring all options and trying to be as creative and out-of-the-box as possible,” he said. “No one on the commission wants to implement service cuts. We know how important the service is to our riders. A large majority use DART to get to work.”

“Having to reduce service is not ideal, and it’s definitely going to impact our riders and none of us want to see that occur, but we have to do something to make DART more sustainable in the future,” Trimble said.

Part of the innovative thinking has already begun with the introduction of services like DART on Demand and FlexConnect, the partnership with Uber and Yellow Cab. Both programs have been successful, he said.

The funding formula was also revamped to put it in line with usage, Trimble said.

“We are constantly looking at innovative and creative ways to reinvent transit and coming up with more efficient and effective services,” he said.

That has included rightsizing some buses, going from 40-foot buses to 30-foot buses or smaller, Trimble said.

DART needs to push the status quo, he said.

“We’re doing everything we can to be efficient, effective and creative,” Trimble said. “We need to be more nimble than we are right now and we need to be more creative than we’ve been to work to reinvent transit and meet the needs of our riders and our member communities.”

DART needs to look at riders’ travel patterns and cater to those needs, he said.

“We need to ask questions,” Trimble said. “We need to challenge each other as commissioners to push the envelope and really try to reinvent transit.”

The business community needs to be an active voice in the conversation about DART’s future, he said.

“When you look at service jobs across the metro — and we have a lot — a lot of the people who do these jobs can’t afford to live in the community where they work, so they rely on public transit to be able to get them to work,” Trimble said. “If these people aren’t able to get to work, the labor issue we currently have is just going to be exacerbated.”

“It’s extremely important for business,” he said. “It’s critical for the workforce and getting people to their jobs. I think a lot of businesses don’t realize there are a lot more people that rely on public transit to get to work than they realize.”

Wanke said it’s critical that the business community be involved in the conversation. It’s that collaboration that will help make DART successful, she said.

“It is important to me that we’re having conversations and working together,” she said. “I’ve seen this community when we have a vision together; we come together and do things well. And when we do things well, we have business, community, government and nonprofits all at the table together.”

“It’s important to view public transit the same way,” Wanke said. “We’re working on investing in all these amenities and building our community in a lot of great ways and we need to make sure everyone in our community has access to those things. How do we create that vision that public transportation is worth investment in, and what does that look like?”

It’s also about ensuring that DART can help businesses address their own challenges, she said.

“We need to continue to understand what’s important to them, their vision and what they need and how we can help them solve those problems so that we’re working hand in hand to create that strong community.

TRANSPORTATION TIMELINE

1866 Use of horsecars [streetcars pulled by horses] begins on Des Moines streets.

1888 Electric-motored streetcars are introduced.

1890 – 1929 Streetcar service operated by Des Moines City Railway Co.

1929 – 1949 Des Moines Railway Co. takes over service.

1938 Gas-powered buses become commonplace, replacing streetcars.

World War II Streetcars make a resurgence as rubber from bus tires is needed for the war effort.

1945 By the end of World War II, buses had resumed service on the city’s streets.

1949 – 1954 Des Moines Transit operates bus service.

1954 – 1973 Iowa Regional Transit Corp. takes over operation of bus service in Des Moines.

1973 – 2006 Public transit in Des Moines is operated by the Metropolitan Transit Authority.

2006 Present Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority assumes operation of the bus system in

the region.

2020 DART launches a pilot project testing electric buses in its fleet.

Electric buses sidelined

DART launched a pilot project in the fall of 2020 to test the performance of electric buses it added to its fleet. The seven Proterra electric buses were pulled from service in the fall of 2022 because of expiring warranties and some structural issues with the buses. Officials with DART said they had been working with Proterra to return the buses to service, but as that plan was being finalized, the company filed for bankruptcy. Officials with DART said they are waiting to see how that proceeds before deciding to move forward with the electric bus pilot.

Michael Crumb

Michael Crumb is a senior staff writer at Business Record. He covers real estate and development and transportation.