Collision ahead for prosperity express?

Our job-generating economy threatens a short supply of affordable housing

KENT DARR Dec 7, 2017 | 3:10 pm

11 min read time

2,588 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Real Estate and DevelopmentGood-time Greater Des Moines has the blues when it comes to the mix of a job-producing economy and the strain that growth places on affordable housing.

Eric Burmeister, executive director of the Polk County Housing Trust Fund, puts it another way. He sees a “train wreck” ahead.

To say that there is tension in the air when the conversation turns to affordable housing in Greater Des Moines would be an understatement.

The majority of affordable housing is located in Des Moines, where city officials are encouraging their booming suburban neighbors to take steps to provide more housing options or relieve some of the financial pressure that Des Moines officials say is the result of hosting the most affordable units in the metro. Many are doing so.

But just building that housing in the suburbs can be a challenge. Greenfield land is expensive, and Congress is threatening to slash or eliminate a range of programs that in the past have provided some financial relief and incentive for developers who build new or rehabbed affordable units.

It is an issue that Burmeister and Kris Saddoris, vice president of development for Hubbell Realty Co., said last month at a public policy forum on affordable housing requires the attention of the entire business community, not to mention public officials.

The Greater Des Moines Partnership sponsored the forum, and given its reputation as a thought leader, it would be safe to say the business community is paying attention, or at least beginning to pay attention.

“As this continues to be a focus of the area, and an area where a broad array of stakeholders engage in, the Partnership will be involved,” said Joe Murphy, the organization’s senior vice president of government relations and public policy.

Capital Crossroads 2.0, which provides a five-year vision on a range of issues in Greater Des Moines, lists several areas around affordable and workforce housing — there is a difference between the two — that deserve attention.

Des Moines officials are taking steps to force the issue.

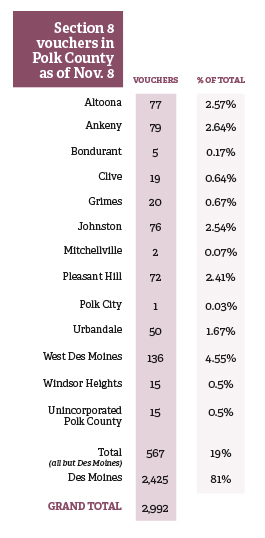

Step one: The city is the conduit for federal Section 8 funds that qualifying individuals use to help defray rent costs both in Des Moines and elsewhere in the metro. In fact, a Section 8 voucher that is secured in Des Moines can pay for housing in West Des Moines — or Denver, for that matter. Des Moines City Manager Scott Sanders wants suburban communities to share in the costs of administering the program, which runs at a deficit due primarily to uncertainty in funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Step two: The city is considering whether to turn operations of its housing programs over to a private company. Doing so could free up local tax dollars that pay a relatively small portion of the $20 million-plus cost of the programs. Federal funds pay the the majority of the costs.

Step three: Sanders hopes to win support for changes in the “fair play” agreement that was adopted by Greater Des Moines communities in 2000 as a way to prevent one city from offering inordinate incentives to lure businesses from another. He wants businesses that cross municipal borders to say how they will accommodate their workers’ housing and transportation needs. The agreement has been under review as the result of a corporate move to Waukee from West Des Moines.

Step four: The city is pressing developers to provide affordable units in housing developments that carry more expensive rents. The City Council is giving some consideration to mandating an affordable housing component in projects that receive city development incentives.

The numbers show that Des Moines has the largest concentration of low-income housing in Greater Des Moines. The Des Moines Metropolitan Housing Agency administers HUD’s Section 8 program in Polk County. The program provides vouchers that help low-income families pay their rents. Of the 2,992 vouchers that were being used on Nov. 8, 2,425, or 81 percent, were being used in Des Moines.

A program administered by the Iowa Finance Authority also distributes low-income housing tax credits that can be used to defray the cost of building or renovating housing units for individuals with incomes at 60 percent or less of the area median income. The formula calls for 20 percent or more of the units in a project to be used for incomes at 50 percent or less of the area median income, with 40 percent or more of the units for individuals or families with incomes at 60 percent or less of area median income. The units must be rent-restricted, and Section 8 vouchers can also be used to pay the rent.

Since 2011, the Iowa Finance Authority has approved $13.7 million in tax credits that have led to the creation of 1,240 units of affordable housing in 23 projects that involved new construction or renovations in Des Moines. Overall, there are 5,716 housing units in Polk County that were built with low-income housing tax credits, with 3,857 in Des Moines, according to the National Housing Preservation Database.

The Polk County Housing Trust Fund, the lead affordable housing advocate in the area, allocates about $2 million a year in state, local, federal and private funds to support the development of affordable units.

And just what is affordable housing, anyway? For the most part, it is housing in which rents are subsidized via a range of federal and state programs. But it also can occur in complexes where rents become affordable — meaning they require no more than 30 percent of household income, by the federal standard — due to age. In other words, the rents drop through an organic process, Burmeister said.

According to a national report, rents in Greater Des Moines have become less affordable over the last decade.

In 2005, Greater Des Moines was the most affordable market in country, according to Apartment List, which aggregates national apartment listings, with 39 percent of renters spending 30 percent or more of their income on rent. Renters above the 30 percent threshold are considered “cost burdened.” By 2016, the number had risen to 46 percent.

Statistics compiled by Polk County Housing Trust Fund place the number of cost-burdened renters in Polk County at slightly more than 48,000.

Burmeister presented the cold data during the Partnership’s housing forum.

- From 2005 to 2015 in Polk County, the median household income of renters rose 8.9 percent, while the median rent increased 19.6 percent, led by rents in downtown Des Moines.

- Seven of the 10 fastest-growing jobs in Central Iowa pay less-than-average wages, and three of those job categories fall below or barely reach the cost of living for a single person.

Federal and state housing assistance is available to households making no more than 80 percent of area median income. In Greater Des Moines, a family of four earning $61,500 a year is at that level, as is a single person earning $43,050. For the record, the state’s workforce housing tax credit program is intended to promote housing for workers who earn 80 percent to 120 percent of area median income.

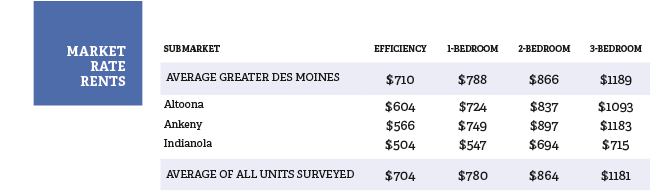

Here are examples from the Polk County Housing Trust Fund of jobs that are on the rise in Greater Des Moines and the rents workers in those jobs can afford at 30 percent of income:

- The average annual income of a customer service representative is $35,160 per year, making a monthly rent of $879 affordable.

- The average annual income of a janitor is $24,070, making a monthly rent of $601 affordable.

- The average annual income of a food service worker is $19,740, making a monthly rent of $494 affordable.

There is strong demand for affordable apartments. According to CBRE|Hubbell Commercial’s 2017 survey of multifamily units in Greater Des Moines, vacancy rates on units that used low-income housing tax credits dropped to 2.1 percent this year from 2.7 percent in 2016. Rents for those units increased between 3.4 percent and 18.5 percent from 2016 to 2017.

The consequences of the flip in recent years from development of affordable housing to more expensive market-rate housing in Des Moines have not been lost on city leaders.

Earlier this year, when Assistant City Manager Matt Anderson and Economic Development Director Erin Olson-Douglas were asked to identify a major trend for 2017, development of affordable housing ranked No. 1.

At the time, 2,700 apartment units were under development in the city; 9 percent were affordable and 91 percent market rate, they said. Balance was needed.

“We need to acknowledge that ‘affordable’ or ‘workforce’ housing is essential for moving downtown’s momentum forward,” they said.

For Burmeister and others, development of affordable housing is necessary for moving the region forward.

Burmeister’s train wreck would be a convergence of several tracks.

The high cost of land in the suburbs — around $35,000 an acre — makes it difficult for developers to build affordable housing and still turn a profit. Land-use policies could change that. The city of Des Moines’ planned implementation of a form-based zoning code that would encourage mixed-use and mixed-income developments along transportation routes is an encouraging step in that direction, Burmeister said.

“Land use drives land prices,” he said. “If a jurisdiction decides that 10 acres is going to be set aside for affordable housing, the price won’t exceed its permitted use; if it isn’t set aside, the affordable housing developer can’t compete with the office developer and the store developer for that same piece of land.” For cities, those commercial developments also generate more property tax revenue than can be pulled from affordable developments because of changes in state law.

The region’s focus on education and workforce development creates an income mix where high-wage earners create services supplied by low-wage earners.

“We know there is some creation of service-level jobs for high-income households. The six-figure plant scientist at Pioneer creates a demand for service-level jobs that are directed to the quality of life that Pioneer is using to create those jobs,” Burmeister said. “One of these times you’re going to end up in a position where you’re going to say, ‘I need workforce that is paying $35,000, $40,000, but they can’t find a place they can afford.’ In terms of changing the audience for this kind of conversation, it needs to be folks that have a vested interest in workforce development. We talk a lot about training, but it’s equally important as to where we are going to house these people.”

And relying on the Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority, which is beset with budget problems, to transport workers long distances to work is not a suitable answer. For one, workers would prefer to live closer to work. DART vans make 17 trips a day shuttling workers to and from Des Moines and Marshalltown to TPI Composites Inc. in Newton.

Add it all up, Burmeister said, and, “To me that’s such an obvious train wreck coming. How do you pretend that somewhere, somehow things are going to work out?”

Des Moines City Manager Scott Sanders might not see a train wreck ahead, but he does see challenges.

For one, a 2013 state law is gradually lowering the taxable valuation of multifamily properties to about 60 percent of full value from 100 percent. Those declining tax revenues put a strain on the city budget, especially when projects use city incentives.

“When (developers) ask for city assistance, the first thing we look at is project-generated revenues,” Sanders said. “It gets to a point where affordable housing is a necessity, a priority and a strategy, but it is harmful to a city budget, so you have to balance that.”

Sanders said the range of state and federal tax incentives that provide direct or indirect support for affordable housing can help soften the revenue blow to the city budget. However, the tax plans that have been passed in the U.S. House and Senate would eliminate or diminish some of those programs, as would lowering tax rates for corporations and the wealthy that frequently buy tax credits to reduce their income tax liability. The House and Senate tax bills would lower the corporate tax rate to 20 percent.

It has been slow going in the ask for contributions to the city-managed Section 8 program, Sanders said. He is asking 12 other cities to make payments based on their populations and shares of Section 8 vouchers used within their borders. So far, Clive, Urbandale and West Des Moines have agreed to participate.

Using the fair play agreement to force a conversation on affordable housing fits in with Sanders’ desire to bring businesses and their dollars to the table in a range of initiatives that they support in concept as a means to enhance cultural amenities that are used to recruit and retain workers,

For example, Sanders supports efforts to create a recreational water trail on the Des Moines River as well as the Connect Downtown initiative that would narrow streets to make them more pedestrian- and bike-friendly. He also expects businesses to pick up the costs.

With fair play, “the real key here is that in the discussion of a business moving from one city to the next, part of that discussion should be what choices the low-income employees will have for housing and transportation,” he said. “That way you are addressing some of the potential conflict right up front. I’m not saying they have to build or fund a DART route, but how will they address such issues if they don’t?”

Urbandale City Manager AJ Anderson is sympathetic.

“It’s a conversation that you can’t avoid or shouldn’t avoid,” he said. “It has a variety of twists and turns to it because obviously one size doesn’t fit all.”

The city of Des Moines runs two affordable housing programs out of one office. Both programs receive the vast majority of their funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The city’s taxpayers will kick in an estimated $368,728 in the fiscal year that begins July 1 out of a total budget of $22.2 million. The Des Moines Metropolitan Housing Agency administers the Section 8 voucher program for all of Polk County. The city’s Housing Services Department manages about 390 city-owned apartment units and an additional 34 single-family homes where rents are charged at approximately 30 percent of adjusted income. All of the housing programs run at a deficit, primarily because of inconsistencies in HUD funding levels from year to year. The city is considering privatizing all or part of the affordable housing programs.

Source: Des Moines Municipal Housing Agency

As of Nov. 16, the Iowa Finance Authority had received 30 applications for low-income housing tax credits, with 10 of those proposing 454 units in Greater Des Moines. Applications for 2018 credits have been requested for projects in Ankeny, Carlisle, Des Moines, Grimes, Norwalk, Pleasant Hill and Urbandale. However, the U.S. House has proposed eliminating another form of low-income house tax credit that can create large blocks of affordable housing. In 2017, the Iowa Finance Authority has received applications for projects in Des Moines and West Des Moines that would create a total of 408 affordable units.

Source: Iowa Finance Authority

Source: CBRE | Hubbell Commercial apartment survey

The impact of low-income housing tax credits in Des Moines

Since 2011, the Iowa Finance Authority has approved $13.7 million in tax credits that have led to the creation of 1,240 units of affordable housing in 23 projects that involved new construction or renovations.

Source: City of Des Moines