A fix for Iowa’s broken individual health market?

Association health plans tee up for 2019 coverage

JOE GARDYASZ Apr 17, 2018 | 4:51 pm

8 min read time

1,963 wordsAll Latest News, Banking and Finance, Business Record Insider, Education, InsuranceNow that the Iowa Legislature and the Trump administration have enacted measures to expand association health plans in Iowa and nationally, state and federal regulators are writing rules to provide new options for many types of business organizations to pursue health coverage plans for their members.

However, Iowa’s top insurance regulator — Insurance Commissioner Doug Ommen — says association health plans alone won’t be enough to fix an individual health insurance market that’s already on life support. Here’s what Ommen and other health insurance experts say to expect ahead of the new laws going into effect, and what it may mean for many Iowa small-business owners.

On April 2, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed legislation that will allow small employers to form association health plans, in an effort to provide new options for lower-cost coverage with fewer mandates.

The U.S. Labor Department in January proposed rules that would make it easier for states to allow new or expanded use of association health plans, following an executive order signed by Trump that encouraged more use of such plans.

Iowa’s new law, Senate File 2349, which becomes effective July 1, authorizes associations or related businesses to form Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangements (MEWAs), which would be regulated by the insurance division.

The legislation, which combined two bills into one — also allows the Iowa Farm Bureau Federation to offer a health benefit plan to its 160,000 members on the premise that the coverage is not technically insurance, so it will be exempt from regulation by the Iowa Insurance Division.

Notably, the non-insurance benefit plans won’t subject Farm Bureau members to federal penalties for not having health insurance, since Congress repealed the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate effective on Jan. 1, 2019, as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act signed by the president in late December.

A lot of moving parts

Ommen said the state measure is not the final answer for a broken individual insurance market that only Congress can truly fix.

“There are a lot of moving parts going on, and what I think is lost in the sound bite of the day is that the Affordable Care Act is just not working,” he said. “There are just some real basic flaws in it. I’ve heard it said by some that when the ACA was passed, the actuaries left the building. But the reality is, there are just things that are built into the actual text of the statute that really are going to make it hard to ever fix without an act of Congress.”

Ommen, whose agency is gathering public comments through April 27 in preparation to write rules governing the non-Farm Bureau AHPs, attempted last year to obtain a waiver from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for a “stopgap measure” following an exodus of carriers from the individual market. He withdrew that request in October, a month after CMS had given it preliminary approval, after Trump intervened personally to stop the request, according to a Washington Post article.

The new federal rule would make it easier for an association to be considered a single multiemployer plan under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Existing associations could continue to offer AHPs, but the proposed changes would enable more AHPs to be regulated under ERISA and rules for large-group health plans.

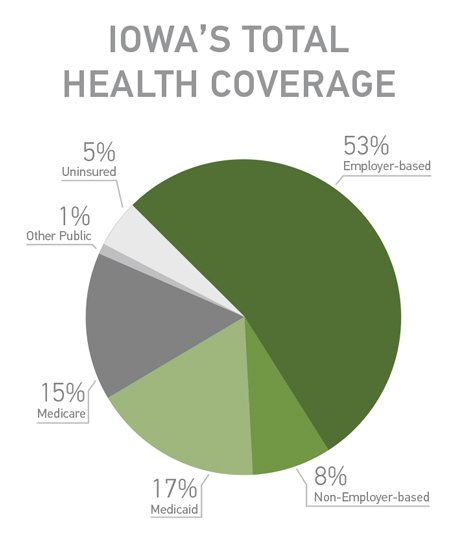

The rate structure of the ACA has driven young and healthier people out of the marketplace, Ommen said. In total, the Iowa Insurance Division estimates that only about 4,000 Iowans are still paying full freight for unsubsidized individual coverage, meaning that about 90 percent of the ACA individual market receives federal subsidies.

“The insurance carriers have lost any incentive to actually keep rates attractive,” he said. “Across the country, there’s more and more incentive to just create your population with subsidized individuals who feel nothing [from premium increases] because other taxpayers are picking up the difference.”

Although some health policy experts say that association health plans could harm the individual and small group markets, {see page 14}, Ommen said he doesn’t see how the individual market in Iowa could be harmed any more than it already has been.

Nevertheless, some state regulators and legislators have been wary of association health plans following significant fraud in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2001, for instance, the Iowa Insurance Division issued an emergency cease-and-desist order to stop Employers Mutual LLC, a Nevada-based entity, from selling phony health insurance policies in Iowa. People who had purchased the company’s policies through employer associations were left holding the bag for millions of dollars in uncovered medical bills.

Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller is among a group of 17 state attorneys general who oppose the proposed federal AHP rule, arguing that association health plans have “a long and notorious history of fraud, mismanagement, and deception.”

“The proposed rule is an unlawful attempt to accomplish by executive rulemaking changes in law and policy that lie within the power of Congress — and that Congress has refused or failed to adopt,” the AGs wrote in a letter providing comment to the Labor Department, in which they urged the rule to be withdrawn.

If the rule proceeds, the Labor Department should hold public hearings to receive input from from affected stakeholders before any regulatory changes are finalized, they said.

‘Certainly there is an interest’

Brian Gillette, chief operating officer and co-owner of Urbandale-based Group Benefits Ltd., said his agents have begun fielding inquiries from clients about forming AHPs. The company works with about 2,000 independent agents that represent about 75,000 individual health clients and nearly 5,000 business clients.

Because the rules haven’t been written yet at either the federal or state levels, “you’re not in a position now where you could determine for any association whether this is a good move,” he said. “But certainly there is an interest.”

Whether an association is a good candidate will be determined largely by the group’s overall health, in contrast with ACA plans, where rates are dictated by demographics, Gillette noted.

“The obvious thing is that if you chose a group that has lower risk … then it’s reasonable to assume there would be serious opportunities to have leverage in rates.”

UnityPoint Health is among the largest Iowa-based organizations supporting an expansion of association health plans. It said it plans to form an AHP for plan year 2019, provided the federal rules can be quickly clarified.

In public comments on the federal rules, UnityPoint Health officials suggested that the department consider broadening the scope of “commonality of interest” to include sole proprietors and contract workers working for eligible employers. It also supports allowing multistate employers to offer plans across state lines in contiguous states.

Loyalty, stability are key

Although the Iowa Legislature enacted a measure a decade ago allowing association health plans, little activity resulted from that, Ommen said. Among the reasons is a requirement written into the statute that associations had to have been in existence for five years prior to 1997. “At the time it may have been a timely requirement, but because there was a date, every year that passed, it made it less and less likely that any organization was going to be formed,” he said.

The Iowa Bankers Benefit Plan provides many lessons for success for an association health plan, Ommen said. The plan, a program of Iowa Bankers Insurance and Services Inc., covers approximately 27,000 members and is in its 40th year of operation. It’s one of just three association health plans regulated by the Iowa Insurance Division currently, along with the Cooperative Welfare Benefits Plan and the PMCI Trust (Petroleum Marketers and Convenience Stores of Iowa Association).

Chad Ellsworth, president of Iowa Bankers Insurance and Services, said the potential for upsetting the stability it has built is a significant concern right now as the rules are being written.

“What’s most key for our plan is the loyalty and stability that we have,” Ellsworth said. “My concern is that once you start changing the rules, do you have unintended consequences? I think we’ve seen that with the ACA. The fear that we would have is that we wouldn’t want to have that sort of disruption.”

Any insurance plan will have years in which its rate increases are higher than it would like to see, Ellsworth noted. “You want to have members who are with you who have that long-term view of things, so they’re not tempted when another association has teaser rates.”

The bankers’ plan is self-funded, a model that is advantageous for an established association plan, but one that could carry too much risk for a plan that’s just getting started, he said.

“In the long run, I think it works better [to be self-funded] because it takes some of the insurance company profit out of it. It can work, but all it takes is one transplant, one premature baby, and all that risk you take on comes back to bite you.”

Study: Association health plans could further destabilize individual market

A study recently released by consulting firm Avalere Health concludes that while association health plans may lower premiums for younger, healthier people, they may increase premiums for others and further destabilize the ACA markets.

“Changes that allow or incentivize healthier individuals to exit the individual and small group market to pursue other, sometimes non-ACA-compliant coverage offerings, could lead to higher costs for those sicker, less healthy individuals and groups who remain behind in the ACA regulated markets,” the study said.

Avalere projects that association health plan annual premiums would likely be $1,900 to $4,100 lower than those in the small group market, and $8,700 to $10,800 lower than in the individual market by 2022, depending on the benefits those plans offer.

Depending on the availability and generosity of association health plans over the next five years, Avalere projected between 2.4 million and 4.3 million Americans would shift to association plans from the individual and small group markets by 2022.

Iowa’s previous association health plan efforts

Before enacting the association health plan bill this session, the Iowa Legislature had considered several measures over the past 15 years to again allow employers to form association health plans in the state, as a means to address rising and increasingly unaffordable health care costs.

In 2007, the Iowa Legislature passed and Gov. Chet Culver signed an association health plan bill advocated by a coalition of business groups and health insurance carriers.

That measure, led by the Iowa Association of Business and Industry and the Federation of Iowa Insurers, allowed members of “bona fide associations” who work for small employers to be treated as one group for the purpose of purchasing health insurance.

The law also allowed insurers to transfer small employers to a lower-cost rate class, provided they establish wellness programs, and authorized insurers to offer premium credits or discounts to smaller employers that offer wellness programs.

Iowa ABI President Mike Ralston said that measure didn’t lead to a new association health plan for ABI members, however.

“We found that, even with the law passed at the time, we could not offer plans more cheaply than Wellmark,” Ralston said. “Then Principal decided to get out of health insurance and that, of course, ended our experiment. We are still glad we tried it and some good came of it, just not a major new health insurance program.”

According to a 2017 issue brief from the American Academy of Actuaries: “It is unlikely that any AHP would be able to achieve the critical mass of enrollees needed to negotiate the deep provider discounts that large health maintenance organizations and insurance companies currently obtain. A more realistic scenario is one in which AHPs ‘rent’ provider networks and pay access fees that depend in part on market leverage and savings.”