Beating the odds

Harry and Pamela Bookey's story of saving the Masonic Temple teaches developers and leaders that a lot can come from the word 'no'

Against the odds, The Temple for Performing Arts has become a lively downtown Des Moines gathering place.

The smell of coffee and the sound of chatter emanates from the Starbucks coffeehouse. Visitors and downtown workers grab New York-style pizza from Centro. And the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines is able to pack the theater on the second floor, while the ballroom on the fourth floor is booked through 2013.

Both student musicians and adult musicians use the building to practice their craft, and there’s hardly any open office space.

The synergy of the place now is obvious and powerful. So much so, that it’s easy to forget that 10 years ago, the Temple was an eyesore that the city wanted to tear down. Business leaders and city officials were working together to create a grand Western Gateway with new buildings surrounding green space. Conventional wisdom was that old buildings such as the Temple would hinder growth rather than spur it.

“When we were doing work on it, we’d see people driving by really slowly, looking at it and shaking their heads, thinking, ‘Man, am I glad I’m not one of them,’” said Pamela Bass-Bookey.

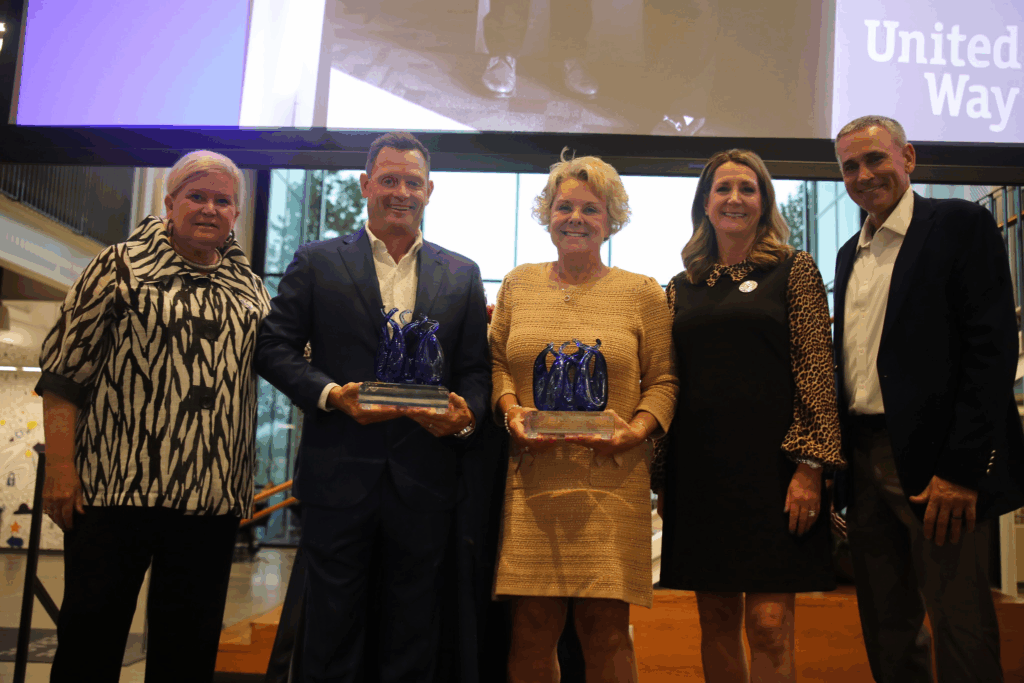

Bass-Bookey and her husband, developer Harry Bookey, were the creative, bold minds behind the Temple’s redevelopment. But if their story teaches developers and business leaders anything, it’s that a lot can come out the word “no.”

“I don’t know if people had expectations,” Bass-Bookey said. “I don’t think anybody had any idea because it was so out of the ballpark from what anybody has ever done. I don’t think anybody had any idea what to expect.”

As the city begins to redevelop Walnut Street from a bus transit mall into a retail and entertainment district, leaders can learn from the Bookeys’ success.

“It takes a vision and courage to turn around an area like that,” said Glenn Lyons, president and CEO of the Downtown Community Alliance (DCA), which is spearheading Walnut Street’s transformation. “It would have been easy to leave (the Temple alone) and let it be torn down. But then Des Moines would have lost something special.”

And much like the Temple, people are wondering what can come from Walnut Street and how the DCA will attract business to the area, Lyons said.

“It takes a special city to have leaders who can look ahead,” he said.

Low expectations

Originally built in 1913, the Masonic Temple was “noted for the opulence of its Grand Lodge with intricate moldings, faux marble columns and elaborate stained glass windows,” according to the Temple’s website. By the late 1980s, however, little of that grandeur was obvious.

With a pawn shop and a wig shop on the first floor and bail bond offices on the third floor, the Temple was on the city’s radar to be demolished under a plan to develop the Western Gateway. In 1997, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places, but even that designation couldn’t save it.

“There was a lot of back and forth about tearing it down — it was assumed it would be torn down,” said Paul Rottenberg, president of Orchestrate Hospitality, which managed the Temple from 2002 to 2011.

Enter developer Harry Bookey and his wife, Pamela Bass-Bookey.

“This was a very contentious building,” said Bass-Bookey. “The preservationists were working hard to save the building, but the city had a plan to remake this area. … There were people submitting plans (to save the Temple), but none of them really had any legs.”

The two 4,000-square-foot ballrooms in the center of the building made it difficult to lease space, Bookey said, adding that “between the cost of construction and the lack of rentable square footage, it was a challenge to get it financed.” Nonetheless, he put together a plan to save the Temple, battled the City Council and eventually won.

Even after the Bookeys secured the site, they continued to face challenges when it came to putting the various pieces of the project together.

“We couldn’t get a restaurateur, which was a key element of leasing,” Bookey said. “We took 10 restaurateurs through here, toured them, and they all told us the same thing: ‘Nobody will come down here at night, so you can’t be open at night; nobody will come down here on the weekend, so you can’t be open on the weekends. But you should do well at lunch.’”

A friend eventually introduced them to a sandwich shop owner — George Formaro — and shortly after that, Centro was born.

The couple also had a hard time reeling in a coffeehouse. “We went to Zanzibar. We went to Java Joe’s and all the other local coffee people,” said Bass-Bookey. “Again, no one thought it was viable; no one thought it would work.”

So they set their sights high and decided the Temple should house the first Starbucks in the state. Starbucks had other ideas. The company was interested in opening a store in the suburbs because Midwest downtown stores were not performing well, Bookey said.

But the couple continued their pursuit, showing off the building to a Starbucks broker. The corporate offices remained undecided for 11 months. “We didn’t know until a month before the Temple opened,” Bookey said, adding that the decision was so contested that then Gov. Tom Vilsack called and spoke with Jim Donald, who at that time was CEO of the coffee company, to help seal the deal.

“Having the Starbucks meant so much. It was a well-known name, and it gave it a lot of credibility commercially,” Bookey said. “(The Starbucks), I think, has had a lot to do with changing the view of the building, but also changing the commercial viability of downtown.”

Effect on the arts

Joseph Giunta, music director of the the Des Moines Symphony, had dreamed of adding an educational component to the orchestra to give Des Moines students a place to learn. Bookey asked him to come and take a look at the building as a possible location for the proposed academy.

“It was quite an unsightly place,” Giunta recalled. “We walked into the main floor; it was dark and dingy and not very attractive. Went to the second floor; it was a big open space filled with offices for bail bondsmen and lawyers, I think. By the time I got to the third floor, my instinct was to turn around. It was just so bad.”

But Giunta and the Symphony signed on to the project shortly after. Here’s why: “When I finally got to the fourth floor and saw the stained-glass windows and the ballroom, that’s when I knew this was a place that had great potential,” he said.

They were later joined by the Iowa Youth Chorus and the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines. Since that time the Civic Center’s and Symphony’s relationships with the Temple have thrived.

“We wanted 100 students the first year, and had 300,” Giunta said. It’s grown from there, with about 450 students currently enrolled. The organization also boasts three youth symphonies, summer camps and other programming.

Thanks to renovations, the Symphony now can practice at the Temple as well. The Bookeys and the organization put new lighting in the fourth-floor ballroom and fixed the acoustics by adding carpet and closing off the room with drapery.

The Civic Center had such a huge initial success with the play “Triple Espresso,” the organization has created a Temple Theater series, which consists of three shows.

Like everything else, the Civic Center’s involvement and initial success was more of a serendipitous moment than a calculated move. Bookey said he originally planned to put a jazz club on the second floor; however, plans were not working out. He then spoke with Jeff Chelesvig, the Civic Center’s president and CEO, who knew an actor who had performed “Triple Espresso” in a renovated Masonic temple in Oregon.

“He asked if we’d be willing to build a black-box theater, and at that point, we were like, ‘why not,’” Bookey said.

“Triple Espresso” was originally scheduled for six weeks and ended up running 18 months, making it the longest-running show in Iowa.

“Right from the very beginning, this place was hopping with people. ‘Triple Espresso’ was the reason this became a hot commodity,” Giunta said. “These are things that we take for granted now, but they were very new 10 years ago. There’s no building like this.”

Now the Temple is a cultural hub, giving students and adults a place to gather and make music. It sits next to the Des Moines Public Library and near the John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park. It’s one of the city’s most popular places to hold weddings and events, with people already booking dates in 2015.

“Knowing in these early days what they had to go through with the City Council, with the neighbors, with the conflicting library people – they really stepped up to the plate in terms of making this happen,” Giunta said.

“It happened because they persevered.”

Sparked development

Surrounded today by trendy restaurants, a sculpture park and some of the city’s biggest employers, the Temple neighborhood is a far cry from what it used to be when the only people in the area at night were teenagers scooping the loop.

“It can’t be stressed enough that no one stayed (downtown) after 5. No one,” said Chris Diebel, who worked for the Bookeys as an intern at the time of the renovation.

Orchestrate’s Rottenberg agreed.

“When people stayed at Hotel Fort Des Moines and walked outside on the weekend, it looked like a bomb had gone off,” he said. “They could walk from the hotel to the East Village and not see a single person.”

Rottenberg admitted that he had his doubts that the Temple would be successful, but that between Iowa’s first Starbucks, Centro’s immediate popularity and the Civic Center’s home run with “Triple Espresso,” the Temple’s tenants turned an uninhabited corner of the community into a place that thousands of people use each day.

“It really woke Des Moines up to how powerful that corner was,” Rottenberg said. “I don’t think you can put a figure on that.”

Restaurateurs eventually took notice, and now the area boasts some of the city’s most popular eateries, including Django, Americana Restaurant & Lounge, Proof and Host. The library was completed in 2006 and the Des Moines Art Center put in the sculpture park in 2009. Some of the city’s largest festivals, such as the 80/35 music festival and the Des Moines Arts Festival, are held there each summer, things the Bookeys never expected to happen but hoped their vision could spur.

“We have three daughters, none of whom live here, and we thought, ‘What can we do to help bring young people here,’” Bass-Bookey said. “I think our vision was the catalyst for literally everything that happened after that.”

“We’re a little biased, but we think it was the seminal event that brought development down here,” Bookey said.