Big, bigger, biggest

Demand for super-sized equipment drives multimillion-dollar upgrade

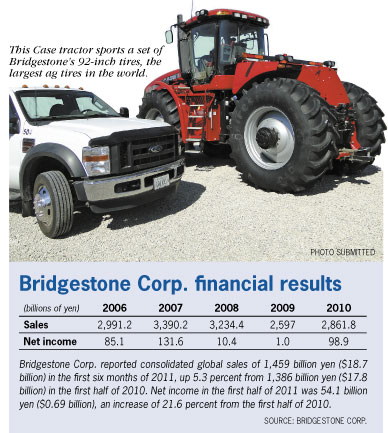

Bridgestone Americas Tire Operations is literally raising the roof – and even lowering the floor – at its sprawling plant just north of Des Moines to make room for new equipment that will enable it to manufacture the world’s largest agricultural tires.

The plant on Northwest Second Avenue is in the midst of a $56.6 million upgrade, which includes installing new tire assembly machines, curing presses and other equipment to produce tractor tires that stand more than 7 1/2 feet tall. To prepare for increased production in the next several years, Bridgestone has increased employment by a net of 260 workers at the plant since April 2010, bringing its Des Moines work force to nearly 1,600 “teammates.”

It’s the sixth major upgrade in the history of the 67-year-old tire plant, which is the world’s largest production facility for agricultural and truck tires. Operating three shifts, seven days a week, the plant uses millions of pounds of rubber each week to produce tires that can weigh up to 500 pounds each. Situated on 105 acres, the plant has been under the Bridgestone flag since 1988, when Japan-based Bridgestone Corp. purchased Firestone Tire and Rubber Co.

The demand is driven by the quest for increased agricultural production, which requires larger and larger pieces of equipment. By 2050, the global demand for food production is expected to increase by 70 percent from today’s output, according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

However, even after Bridge-stone completes the upgrade to its Des Moines factory, it will still face a 30 percent gap between output and demand for agricultural tires, said Ken Allen, president of Bridgestone’s North America agricultural tire division. The plant produces about 95 percent of the agricultural tires that Bridgestone sells in the global market.

“What we have is this ever-increasing evolution of larger equipment, the volume being handled, and more and more applications,” Allen said. As a case in point, Allen noted that Deere & Co., one of his division’s largest customers, this fall introduced the biggest rollout of new products in its history. “Part of that (rollout) included larger tire options, and those larger tire options were on higher-volume tractors,” he said.

Bridgestone revamped its agricultural tire strategy after losing money in that segment for much of the first decade of the new millennium. Its focus is now primarily on the production agriculture market, though it still supplies smaller producers.

“We realized that we could not continue in a loss position; we really had to change our business,” Allen said.

Bridgestone plans at least $20 million in annual capital investments in the plant in the next several years and is developing further plans to address its production gap, Allen said.

“What they are right now is premature to talk about, but be very assured that our plan is to satisfy the demands on our brand,” he said.

Bigger machines, bigger tires

For agricultural tire replacement sales, the company primarily targets the largest U.S. producers, the 300,000 or so farm operations that gross more than $250,000 per year, and it also exports agricultural tires to 60 countries. “We also have indirect export because many manufacturers are engaged in export activities, and we have to follow that product no matter where it goes and be able to service it,” Allen said.

Though demand for the construction equipment tires that are produced by the plant leveled off during the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, demand for agricultural tires did not dip, and the number of tire choices available has continued to grow. The company’s Firestone brand agricultural tire sizes are organized into a matrix that currently consists of 11 rows and nine columns, with 53 tire sizes currently available. As larger equipment is built, new rows are added to accommodate larger tire sizes.

“Traditionally, we have only added one row every 10 years or so,” Allen said. “Now we are faced with adding two rows at the same time.”

Skilled tire builders using the newest 105-inch tire assembly machines (TAMs) can produce about 10 tires per eight-hour shift at full capacity, compared with about 16 per shift for a 90-inch machine. Overall, the agricultural tire plant’s assembly machines are far less automated than similar machines at a passenger-tire plant, which typically produce 13 to 16 times more tires.

“So our customers might say, ‘Why am I having a problem getting tires? I’m not making any more tractors than I used to.’ But (those larger tire sizes) have diminished our capability,” Allen said. Named for the size of the opening it has, a 105-inch TAM can make tires up to the maximum size now available in the market, which is 92 inches in diameter.

New technology

The plant has installed the first of four 105-inch TAMs that are part of the upgrade. Each of the machines will occupy about 20,000 square feet, the same amount of floor space as three smaller TAMs. The company will also install 21 105-inch tire curing presses, which necessitated lowering the floor by 12 feet and raising the roof by 16 feet in that part of the plant.

The presses use heat and pressure to cure, or “vulcanize” the rubber in the assembled tire, which until that step is still just layers of soft rubber sheets wrapped around steel belts.

To accommodate the new machinery, plant personnel removed more than 15,000 tons of equipment from approximately 250,000 square feet of floor space, said Greg Halford, the plant’s manager.

Bridgestone is using several local contractors for the plant renovation project, including The Weitz Co. and Neumann Brothers Inc., as well as some out-of-state contractors with specialized skills in the tire industry.

In August, the Iowa Economic Development Authority approved a $500,000 loan from the Grow Iowa Values Fund and job-training funds of up to $1.6 million through the Iowa Industrial New Jobs Training Program, the latter of which is repaid from withholding taxes the state collects on the new jobs. The That same month, the Polk County Board of Supervisors approved a $50,000 zero-interest loan and a $50,000 forgivable loan to Bridegestone as an incentive for the project.

Approximately 200 of the plant’s workers are now in training to become fully qualified tire builders, a complex process that takes from six to 24 months, Halford said. The number of employees in training is “very high because the plant’s ramping up production,” he said. Each tire builder is paid on an incentive basis, based on the number of tires built per shift.

The new TAMs will enable Bridgestone to produce tires with an “advanced deflection design” (AD2), which reduces the degree of soil compaction caused by heavier equipment.

“That product is as much an improvement in performance as when we went from bias to radial tires,” Allen said. The company is working with some farmers just outside Des Moines who are early adopters of the tires.

The Des Moines plant also produces slab rubber that’s shipped to other Bridgestone plants as well as sold to other tire companies. The company’s only other solely agricultural tire plant is located in Spain. It also has integrated plants, which produce agricultural tires in addition to other types of tires, in Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Japan and South Africa.

Though more agricultural tire production may take place overseas as those markets evolve, “North America is usually where the highest-capacity, most sophisticated equipment is first produced,” Allen said. “So from a global standpoint, we’re going to have the first look at it.”