The Elbert Files: Roadside Iowa

I’m a sucker for roadside attractions.

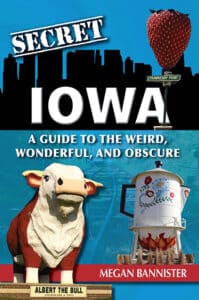

When I saw the new book “Secret Iowa: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful and Obscure” ($27, published by St. Louis-based Reedy Press), I had to have it. The author, Chicago native Megan Bannister, came to Des Moines more than a decade ago to study journalism at Drake University and stayed.

The 184 pages include the usual Iowa suspects: Albert the Bull in Audubon, Snake Alley in Burlington and Dubuque’s Fenelon Place Elevator.

But the nearly 100 entries also spotlight several curiosities that were new to me. For example, the Marshalltown cemetery’s concrete “mourning chair” – common in 19th-century graveyards, Bannister wrote – and the home in Charles City where feminist Carrie Chapman Catt “spent her formative years.”

Bannister introduced me to Iowa’s “whacky arachnid,” a spider sculpture in Avoca that consists of the body of a Volkswagen Beetle held aloft by eight legs of welded, steel pipe. It appears right after Grinnell’s 60-foot stack of 200 rusted wagon wheels that resemble a giant menorah.

Another entry involves the spooky history of Madison County’s famous Roseman Covered Bridge, which figured prominently in Robert James Waller’s “Bridge of Madison County” novel and the subsequent movie. You’ll have to read “Secret Iowa” to get the full story of two 19th-century disappearances at the bridge, one involving romance, the other centered on crime.

There are circus stories, including composer Karl King, who wrote more circus music than anyone, including songs for Barnum & Bailey and Buffalo Bill Cody, before taking a job conducting the Fort Dodge Municipal Band in 1920 and helping to write Iowa’s 1921 Band Law, allowing cities to levy a small tax to support local music.

Two stories involve elephants. Baby Mine was a young elephant promoted by the Des Moines Register and purchased with donations from Iowa children for the Depression-era 1929 Iowa State Fair. An elephant of a different sort made of fiberglass originally appeared at the 1964 Republican National Convention before it was painted pink and installed outside the Pink Elephant Super Club in Marquette. “Pinky” even impressed President Jimmy Carter in 1979, when he witnessed the colorful pachyderm being towed on giant water skis.

Finally, Bannister has a fresh take on the Cardiff Giant, a favorite 19th-century hoax.

The giant was carved from a huge piece of Fort Dodge gypsum during the 1860s for prankster George Hull, a New York agnostic who used it to foil a literalist minister who argued a Biblical quote about giants was true.

Hull buried the sculpture on a farm near Cardiff, N.Y., where it was “discovered” a year later and proclaimed by authorities to be the mummified remains of a giant human. The fake was put on display and sold to a touring sideshow.

Eventually the ruse unwound, and the Iowa origin of the gypsum was discovered. But that did not stop gawkers from paying to see the giant stone as it moved from sideshows to museums, before winding up in the 1930s south-of-Grand home of Des Moines Register publisher Gardner “Mike” Cowles.

His 1985 memoir “Mike Looks Back,” revealed that his 7-year-old son and playmates smashed a delicate part of the giant’s anatomy with a hammer. Cowles said a craftsman repaired the damage before he sold the artifact to a museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., where it resides today.

Bannister does not mention the Cowles connection or the damage to the original statue, but she added a piece of information I did not know.

She wrote that in 1980 sculptor Cliff Carlson created a duplicate – a fake of the fake – that resides in Fort Dodge’s Fort Museum and Frontier Village. A photo shows the newer giant with a fig leaf covering any evidence of injury that might have occurred to the original.

Dave Elbert

Dave Elbert is a columnist for Business Record.