Traffic jam comes early

DOT looks to ease unexpected I-235 congestion on west side

PERRY BEEMAN Jul 24, 2015 | 11:00 am

13 min read time

3,120 wordsBusiness Record Insider, TransportationEDITOR’S NOTE:

Greater Des Moines’ population is projected to grow by 50 percent by the year 2050. Our question — what does the addition of 250,000 people mean for traffic on Interstate 235? It’s the city’s main artery transporting commuters and a significant share of goods. Sure, our existing “traffic congestion” might be deemed laughable by residents in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York. But our ease of travel, with many commuting in just 15 minutes, is also one of the great quality-of-life selling points for the city. Senior Staff Writer Perry Beeman covered the reconstruction in the early 2000s and remembered capacity warnings from planners. He thought it would be interesting to see how the traffic projections, made then, lined up with what we are seeing today. Here’s the deal — many traffic counts at spots along I-235 are already worse today than what was originally predicted for 2020 – particularly on the west side. But, let’s be clear, I-235 isn’t grinding to a 24/7 standstill anytime soon. Yet, with suburbs’ populations growing faster than originally projected, and the freeway sporting three lanes in each direction instead of the originally proposed four, the need to begin work on projects to ease congestion is more pressing. And from all appearances, widening the interstate won’t, and according to local officials, shouldn’t, be one of them.

— Chris Conetzkey, editor of the Business Record

The west end of Interstate 235 is already seeing traffic congestion worse than what was predicted for 2020, state records show.

The freeway crosses through the heart of Des Moines, delivering both workers and goods to the city’s growing downtown area and serving suburbs that are among the fastest-growing cities in the state.

So how the freeway operates — and how easily vehicles can get around — is a big part of the local economic development picture.

Greater Des Moines is one of the few areas in Iowa experiencing steady growth — not a boom by any means, but modest, sustained growth. The area is expected to grow to 750,000 residents by 2050, up 56 percent from 480,000 in 2010.

That makes the future of I-235 critical.

The latest version of the freeway, a $430 million project finished in 2007, is smaller than engineers wanted. They warned, as construction approached in 2001, that the freeway would have capacity problems within 13 years, and that local leaders would have to look to car pools, bus service and traffic management to keep freeway traffic moving.

Instead, serious congestion arrived by 2012 — five years after construction on the new freeway was completed, records show. The latest projections from the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization note that unless actions are taken to reduce traffic on the freeway or at least make it flow more smoothly, congestion in 2020 will be significantly worse than originally predicted, with stop and go traffic or gridlock happening at times at major west-side interchanges. The risk of accidents will rise, too.

A key state engineer said the situation isn’t surprising, given local officials’ decision to call for a smaller freeway design.

“That is what we were asked to build, and that is what we built,” said Scott Dockstader, who directs the Iowa Department of Transportation’s district office for Central Iowa and was instrumental in the freeway reconstruction project.

Basically, engineers wanted four lanes in each direction, plus merge lanes. They got three lanes plus merging, in large part because local neighborhood leaders and elected officials wanted to prevent the loss of a large number of homes.

Trouble comes early

Now we’re seeing the aftermath — way sooner than expected.

“In general, we are over projections in West Des Moines, and under in Des Moines,” said Dockstader. “During peak periods, we have lower levels of service — stop and go,” he added.

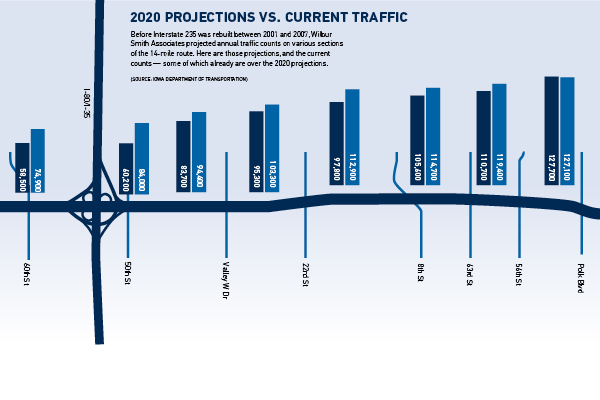

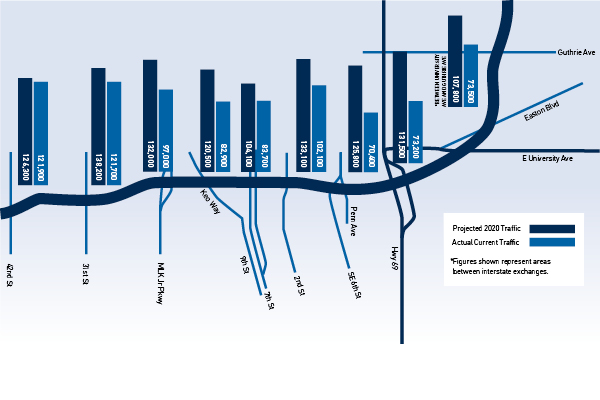

Traffic is far higher than expected on the west side, but still under the 2020 projections on the east side. (See map, p. 10-11.)

For example, the freeway study predicted about 60,200 vehicles a day at West Des Moines’ 50th Street in 2020, but that stretch now has 84,000 vehicles a day — 40 percent above the projection for 2020.

On the other hand, traffic near Keosauqua Way downtown was projected to be 120,000 by 2020. With five years to go, it’s at 82,900.

Dockstader said a key reason for the crunch is the explosive growth of some suburbs. Records show a few suburbs have grown even faster than expected.

For example, the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) predicted in 1999 that Waukee would have 9,436 residents in 2020. It already has 17,077 and is one of the fastest-growing cities in the state. The same study expected Clive’s population to hit 12,600 in 2020; it’s 16,590 now.

With Greater Des Moines’ population marching toward 750,000 by 2050, transportation leaders are taking action to make it easier for employees and shipments to get around in the future.

Stop-and-go traffic already

Transportation officials see challenges that won’t need to be fixed tomorrow but are making them feel pressure to plan for what seems like inevitable work to improve traffic.

The state last year completed a study on adding traffic signals at some freeway entrances to pace traffic, with several spots just west of downtown as likely targets. The freeway ramps were built to handle the devices in a system the engineers call ramp metering.

The Iowa Department of Transportation also may lower speed limits in the heart of the freeway to make it safer, using digital signs that can change speed limits based on weather and traffic conditions, said DOT director Paul Trombino.

None of those possible changes will happen soon. But the discussions are getting more serious now.

Ramp metering is a ways off, if it’s approved at all. “We’re not looking at anything for the next 10 years,” Dockstader said.

Todd Ashby, executive director of the MPO, said he doubts any major I-235 construction would occur before 2050, except the mixmaster work already planned and work related to possible ramp metering.

The state is unlikely to ever widen the freeway, Trombino said, because it would take too many houses and disrupt neighborhoods.

“My gut is I don’t want to disconnect any more,” Trombino said. “I’m not thinking 235 gets any wider. What happens is it separates the neighborhoods.”

In fact, Trombino said he questions whether I-235 should have been built where it is at all — dividing neighborhoods that at the time had low-income residents who largely were racial minorities.

Jeff Speck, an urban designer and smart-growth advocate who has spoken to Des Moines audiences in recent months, said “induced demand” means that it would be fruitless to try to build more lanes to ease congestion.

Basically, induced demand means that if you build more lanes, more people use the road because they think it will be a smooth ride, and the freeway quickly becomes clogged again.

In a recent blog, Speck cited an analysis of dozens of previous studies that found that “on average, a 10 percent increase in lane miles induces an immediate 4 percent increase in vehicle miles traveled, which climbs to 10 percent — the entire new capacity — in a few years.”

So rather than look for a way to build its way out of the problem, the state, with its local partners, is looking at ramp signals, the message boards already installed, the eventual advent of driverless cars, and other ways to add capacity to what already is in place, Trombino said.

In addition to pacing traffic by using ramp signals, the state also might consider varying speed limits along the freeway depending on traffic and weather conditions. Digital signs would post the current speed limit. That would slow traffic, making people feel safer and encouraging more motorists to use the freeway, Trombino said.

How did we get in this situation?

What we are seeing now — already — is the result of a turn of events that started in 1989. The state knew I-235 needed to be reconstructed. It was aging, had dangerous left-hand exits, and clearly wasn’t going to be able to handle future traffic.

A consultant suggested replacing I-235 with a wider model with effectively four through lanes of traffic on both sides, an idea that drew “very little support” because it would have meant demolishing many houses, said Dockstader. A series of studies led to a 1999 plan to build a narrower-than-proposed version mostly within the old right of way.

Engineers warned that local officials would need to find some way through a combination of ramp metering, flexible working hours, expanded bus service, car and van pools, digital signs, and better management of crashes and vehicle breakdowns if they wanted to cut rush hour traffic by 10 percent before 2020 arrives.

No one seems to know how we are doing on that 10 percent, partly because it’s hard to know when to start the clock.

“They didn’t set a base line,” said Dylan Mullanix of the MPO. “That’s been an ongoing debate. Ten percent of what? That’s kind of a fluffy figure.”

Dockstader couldn’t say how the area is doing on reaching the 10 percent goal.

The freeway reconstruction ran from 2001 to 2007. The northeast mixmaster was overhauled in 2008 and 2009 and is in line for more improvements.

Signs of trouble

In the years since the freeway reconstruction, technology has made it far easier for planners to check congestion on the freeway. Thanks to the world of mobile phones, the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization now has access to the same type of up-to-the-minute data that lets Google show traffic problems on its maps. In addition, the Iowa Department of Transportation has a large network of cameras along the freeway. Those views are available to anyone with Web access.

The MPO’s latest analysis of various data this year found some trouble spots.

Data from Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays found that eastbound traffic between Valley West Drive in West Des Moines and 56th Street in Des Moines is between 67 and 85 percent of free-flow speed during the morning rush hour.

The westbound traffic is even worse, with speeds at 50 to 67 percent of free-flow speed between Pennsylvania Avenue in Des Moines and 73rd Street in West Des Moines.

An MPO map of parts of the city with severe congestion levels during rush hour already included stretches near 56th Street, 31st Street, and Martin Luther King Parkway in Des Moines, and 50th Street in West Des Moines in 2010.

By 2020, areas near 50th Street and downtown Des Moines are projected to be at the lowest service rating transportation officials give, meaning the highest congestion.

By 2030, trouble spots during peak times are expected to stretch nearly from Keosauqua Way to 73rd Street, with a few breaks, with parts of that stretch falling into the worst category by 2040.

Outside of the rush hour, congestion is considerably less at times. Yet daily counts are generally well over projections in western Des Moines and the western suburbs.

More crashes

The design of the reconstructed freeway was intended to remove safety problems, including left-hand exits that were part of the original freeway design and unpopular from the time the route first opened in stages during the 1960s. But the growing traffic has contributed to a growing number of crashes.

I-235 runs east-west through much of the metro, but bends to go north-south on the east side of Des Moines.

The number of crashes grew from 320 in 2008 to 354 in 2013, with the biggest share coming in the southbound and westbound legs of the freeway, records show.

The areas around 63rd and 73rd streets have been particularly dangerous, though the state added a merge lane between 63rd and 73rd that is supposed to make the stretch safer.

The westbound stretch between 31st and 63rd has a crash rate above the statewide average, as does the section between 63rd and 73rd.

The western stretches of the freeway see many rear-end collisions, the state reports.

Suburban growth fuels rush-hour congestion

Why is the freeway now more congested than predicted on the west side? Some population figures might give some perspective.

Waukee’s population grew 236 percent between the completion of the freeway study in 1999 and 2013 census estimates. Urbandale grew by 49 percent; West Des Moines, 37 percent; Clive, 42 percent; and Des Moines, 9 percent.

In 1999, when the freeway study was done, the MPO projected the Greater Des Moines population at 505,414 in 2020. Now, the organization predicts a population of 558,000 by then.

Does mass transit hold the answer?

When the Iowa Department of Transportation and its consultants agreed to a slimmed-down version of the original freeway proposal, they made it clear that Greater Des Moines would have to find ways to siphon at least 10 percent of the traffic from the freeway. The idea was to use things like entrance ramp signals, digital signs, the highway helper vehicles that respond to breakdowns and accidents, cameras aimed at traffic, and other techniques to help smooth traffic on a route that, by design, was destined for heavy congestion by 2020.

Of course, in the middle of the discussion about the $430 million freeway was possible expansion of services offered by what is now called the Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority, or DART.

Elizabeth Presutti, general manager of the Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority, notes that ridership has been steadily climbing in recent years. DART has noticed, however, that express routes — a key to taking heat off the freeway — have lost riders lately. That most likely is because gas is cheaper, but also because road construction in some areas made it harder to get to bus stops, Presutti said.

When DART starts another reassessment of its long-term plans later this year, the staff and board will be looking at ways to change the express routes to make them more enticing to commuters. Already, some cities, including Altoona, have worked with DART to add services that can help get express riders the rest of the way to their destination.

DART already has made many changes that help with freeway congestion — or at least are giving area residents another option to driving alone on I-235.

For starters, many routes now run well into the evening, something that wasn’t the case before the freeway was rebuilt.

DART also has deployed 92 vans that carry 670 commuters in a ride-sharing system. Presutti said DART theoretically could add as many vans as people want — they pay for themselves through the fees charged to riders.

“This is the 20th anniversary of RideShare,” Presutti said. “Demand ebbs and flows with the price of gasoline. But we have riders from Lamoni, we have reverse commutes to Pella and Newton.”

DART also has 118 full-size buses, 30 smaller buses and 108 RideShare vans.

Another potential way to relieve traffic on I-235, by offering bus rapid transit, has run into political trouble and an uncertain future. Local elected officials have raised questions about the expense of offering DART’s first bus rapid-transit route — the train-like service on rubber-tire buses on a loop between downtown and Ingersoll and University avenues — or perhaps another route. Business leaders have been meeting to gauge private support while city managers meet to discuss whether local city councils are likely to support the project.

“We had thought we had support,” Presutti said. “Now we are checking to see if it is there.”

A long-term option would be to offer several such routes, perhaps on Southwest Ninth Street, Martin Luther King Parkway and Douglas Avenue, in addition to the initial proposal of Route 60, the University/Ingersoll/downtown loop.

Bus rapid transit, one of the top priorities of the Greater Des Moines Partnership, uses regular buses equipped with devices that extend green lights, which speeds trips. The buses would have their own branding, and improved shelters with digital displays of arrival information.

If bus rapid transit were successful, that might in turn set up another discussion of light rail, an idea that was deemed infeasible because of Greater Des Moines’ population, considered in the midrange of cities. The population is expected to grow to 750,000 by 2050.

Presutti also hopes that a new mobile application, texting system and phone service that provide continuously updated schedule and arrival information will help boost ridership.

DART plans to roll out special promotions to try to boost annual ridership to 5 million, from 4.7 million.

Trombino: I-235 was bad idea

Paul Trombino, the Iowa DOT director, shocked some recently when he told an Urban Land Institute Iowa audience he isn’t sure I-235 should have been built in the first place.

First of all, if Iowans had known what the operation and maintenance costs would have been over 50 years they would have balked at paying for it.

But there was another societal issue.

“I don’t know if 235 was the right decision for the movement of people,” Trombino said. “A lot of those roads should be local streets. A freeway causes a disconnect.”

Trombino knows I-235 cut through neighborhoods — in many cases minority, low-income neighborhoods in which the residents lacked the political power to fight the plan.

“Long term, did it serve the community the best?” Trombino asked. “That was a vehicle decision.”

What is ramp metering?

Ramp metering is a system of using traffic signals to pace cars entering a freeway. It helps increase speeds and reduce accidents by preventing motorists from bunching up. Here’s an FAQ from the Arizona Department of Transportation. http://bit.ly/1CCueQm

The challenge: We love our vehicles

The Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization took a comprehensive look at Greater Des Moines’ transportation scene in its “Mobilizing Tomorrow” report released last November.

The report made one thing clear — local residents are addicted to their vehicles.

In Greater Des Moines, residents make 92 percent of their trips in a personal vehicle, with an average trip covering 15 miles in 25 minutes. Just 5.1 percent of households locally are without a vehicle; the national average is 8.9 percent.

That means a very small minority are riding the bus, walking or biking to get around.

Solutions:

- Varying speed limits along the freeway route, using digital signs that could change based on weather conditions or traffic.

- Technology that will take over control of vehicles.

- Adding signals at on-ramps that pace traffic coming onto the freeway (ramp metering), especially between the west mixmaster and University Avenue.

- Better use of message boards.

- Car and van pools.

- Flexible work hours and telecommuting.

- Bus rapid transit, possible light rail later.

Expanding southeast and southwest connectors.